Introduction

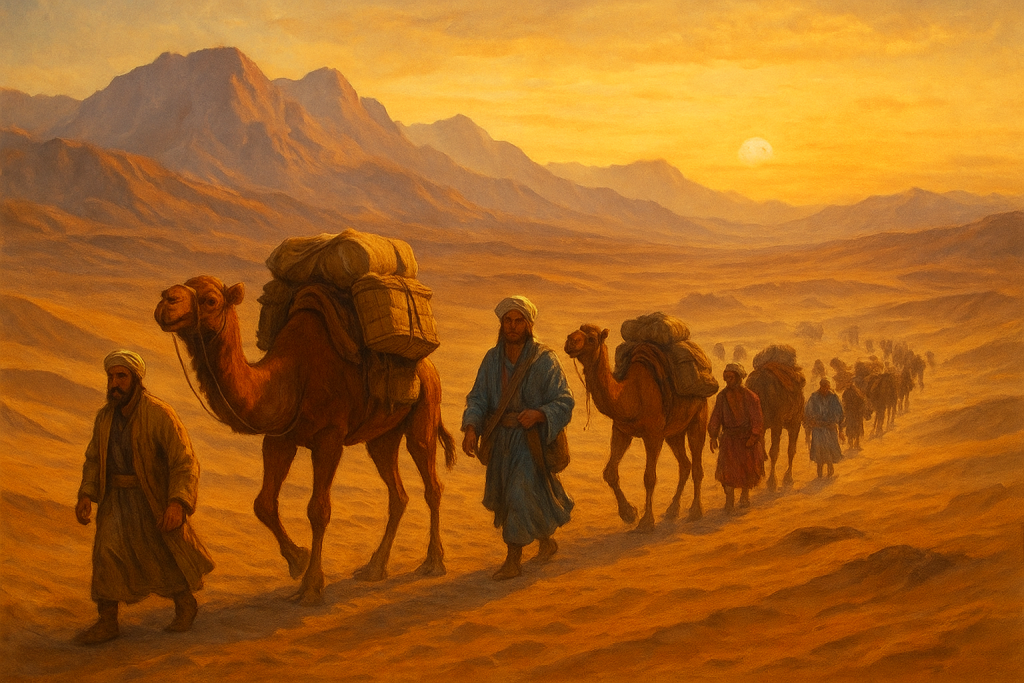

Long before airplanes, cargo ships, and digital markets connected the world, a sprawling network of trade routes stretched across Asia, the Middle East, and Europe. This vast system, known as the Silk Road, was not a single road but a complex web of overland and maritime paths that carried goods, ideas, religions, and technologies across continents.

From the Han Dynasty of China to the Roman Empire, the Silk Road was the beating heart of early globalization — a lifeline that linked East and West for more than 1,500 years.

Its story is not merely one of commerce, but of cultural fusion, human ambition, and the exchange of knowledge that helped shape the modern world.

Origins of the Silk Road

The Silk Road emerged during the Han Dynasty in China around the 2nd century BCE, when Emperor Wu (Wudi) sent his envoy Zhang Qian westward to establish diplomatic and commercial contact with Central Asian kingdoms.

Though Zhang Qian’s initial mission failed, his reports about the lands beyond China — filled with fine horses, new crops, and advanced civilizations — inspired a vision of connection.

Soon, Chinese merchants began trading silk, a highly prized textile made from the cocoons of silkworms, with peoples in Central Asia, Persia, and eventually the Mediterranean world.

The term “Silk Road” was actually coined much later, in 1877, by the German geographer Ferdinand von Richthofen. Yet the name perfectly captures what silk represented: a symbol of wealth, prestige, and international exchange.

The Network That Spanned the World

The Silk Road was not one continuous road but a network of interconnected routes that stretched more than 7,000 kilometers (4,300 miles).

It included two main branches:

- The Overland Route, which started in Chang’an (modern-day Xi’an, China) and crossed the Taklamakan Desert, Pamir Mountains, and Iranian Plateau before reaching the Mediterranean.

- The Maritime Route, often called the Maritime Silk Road, which connected Chinese ports like Guangzhou to Southeast Asia, India, the Arabian Peninsula, and East Africa via the Indian Ocean.

Along these routes, countless cities flourished as hubs of trade and culture, including:

- Samarkand and Bukhara in Central Asia,

- Merv in present-day Turkmenistan,

- Kashgar at the western edge of China,

- Baghdad and Damascus in the Islamic world, and

- Antioch and Constantinople in the Mediterranean.

Each acted as a caravanserai — a marketplace where merchants rested, traded, and exchanged stories and ideas.

Goods That Traveled the World

While silk was the most famous product, it was only one of many treasures that crossed the Silk Road.

From East to West

- Silk – coveted by Roman elites and often traded for gold.

- Porcelain – prized for its delicacy and craftsmanship.

- Tea – which would later transform European culture.

- Paper – invented in China and later spread to the Islamic world and Europe.

- Gunpowder – first developed in China, its knowledge spread slowly westward, changing warfare forever.

From West to East

- Glassware – from Rome and the Middle East.

- Precious stones – such as lapis lazuli from Afghanistan and amber from the Baltic.

- Wool, linen, and dyes – highly valued in Asian markets.

- Wine, olive oil, and spices – from the Mediterranean and India.

The trade went beyond goods. It was about the movement of ideas — technologies, languages, religions, and even diseases traveled alongside the merchants.

The Silk Road as a Bridge of Civilizations

Cultural Exchange

The Silk Road became a corridor of cultural transmission.

Artists, craftsmen, and musicians carried their traditions along the routes, blending Eastern and Western styles.

For instance:

- Persian motifs influenced Chinese ceramics.

- Indian sculpture inspired Buddhist art in China and Japan.

- Greek and Roman techniques found echoes in Central Asian architecture.

Religious Spread

Perhaps the most profound exchange was spiritual.

The Silk Road became a pathway for world religions:

- Buddhism spread from India through Central Asia into China, Korea, and Japan.

- Christianity (especially Nestorian Christianity) reached as far as China.

- Islam, after the 7th century, spread rapidly along trade routes into Central and Southeast Asia.

The ruins of monasteries, stupas, and temples found along the Silk Road — especially in Dunhuang, Turpan, and Bamiyan — still bear witness to this religious melting pot.

The Role of Empires in Shaping Trade

Trade along the Silk Road was heavily influenced by the rise and fall of powerful empires that provided security and infrastructure.

The Han Dynasty (206 BCE – 220 CE)

It laid the foundation for east-west commerce, promoting silk trade with the Parthian Empire and the Roman world.

The Roman Empire (27 BCE – 476 CE)

Romans imported silk and spices from the East, paying with gold and silver. Roman authors like Pliny the Elder complained about the outflow of wealth, calling silk “the shame of Roman luxury.”

The Tang Dynasty (618–907 CE)

Often called the “Golden Age” of Silk Road trade, the Tang era saw an explosion of foreign merchants in Chinese cities. Chang’an was a cosmopolitan metropolis of Persians, Arabs, and Sogdians.

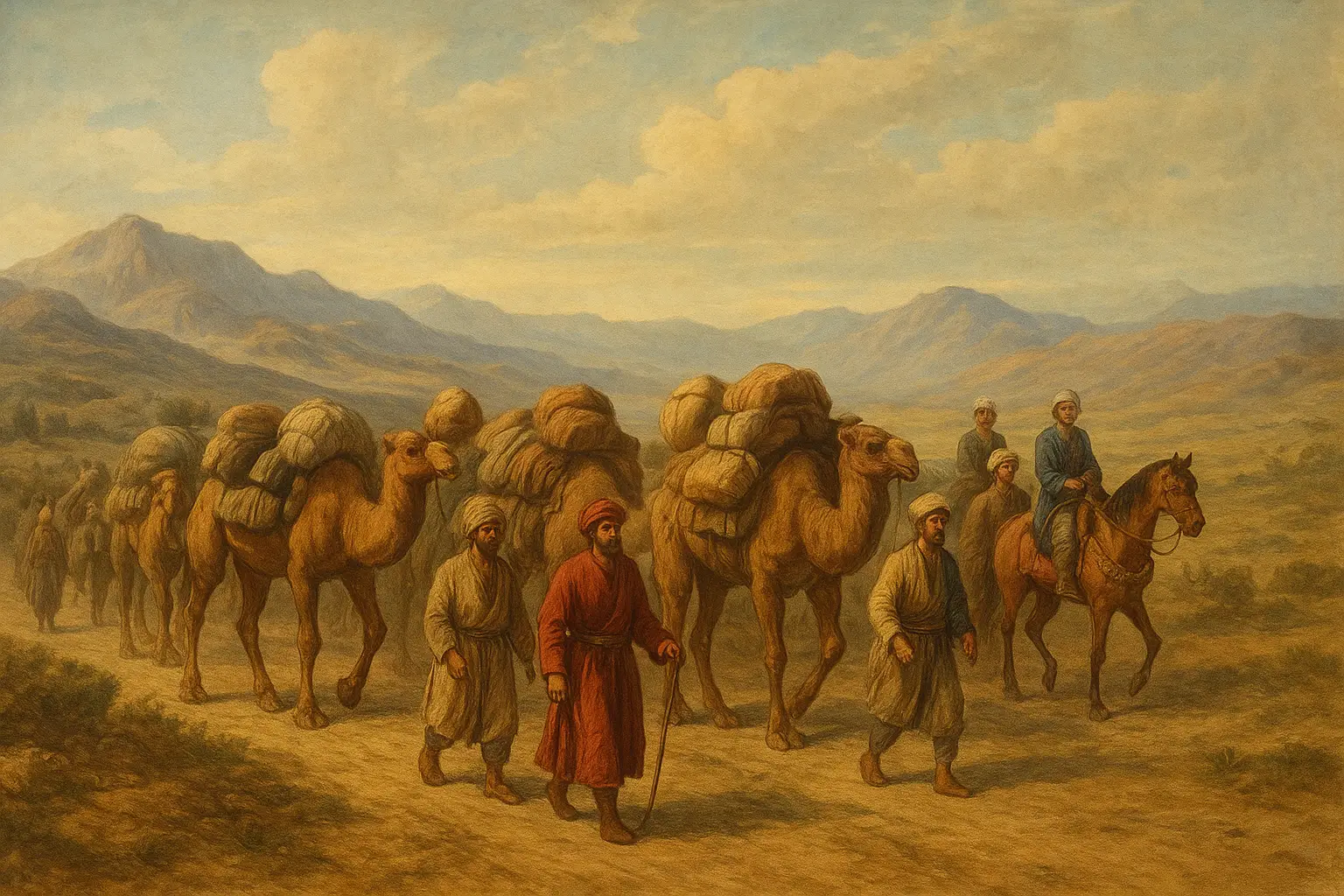

The Mongol Empire (13th–14th centuries)

Under Genghis Khan and Kublai Khan, the entire Silk Road came under unified control for the first time.

The resulting stability — known as the Pax Mongolica — allowed merchants like Marco Polo to travel safely from Venice to China.

The Mongols encouraged communication, established postal stations, and protected caravans — ushering in one of the greatest eras of international trade.

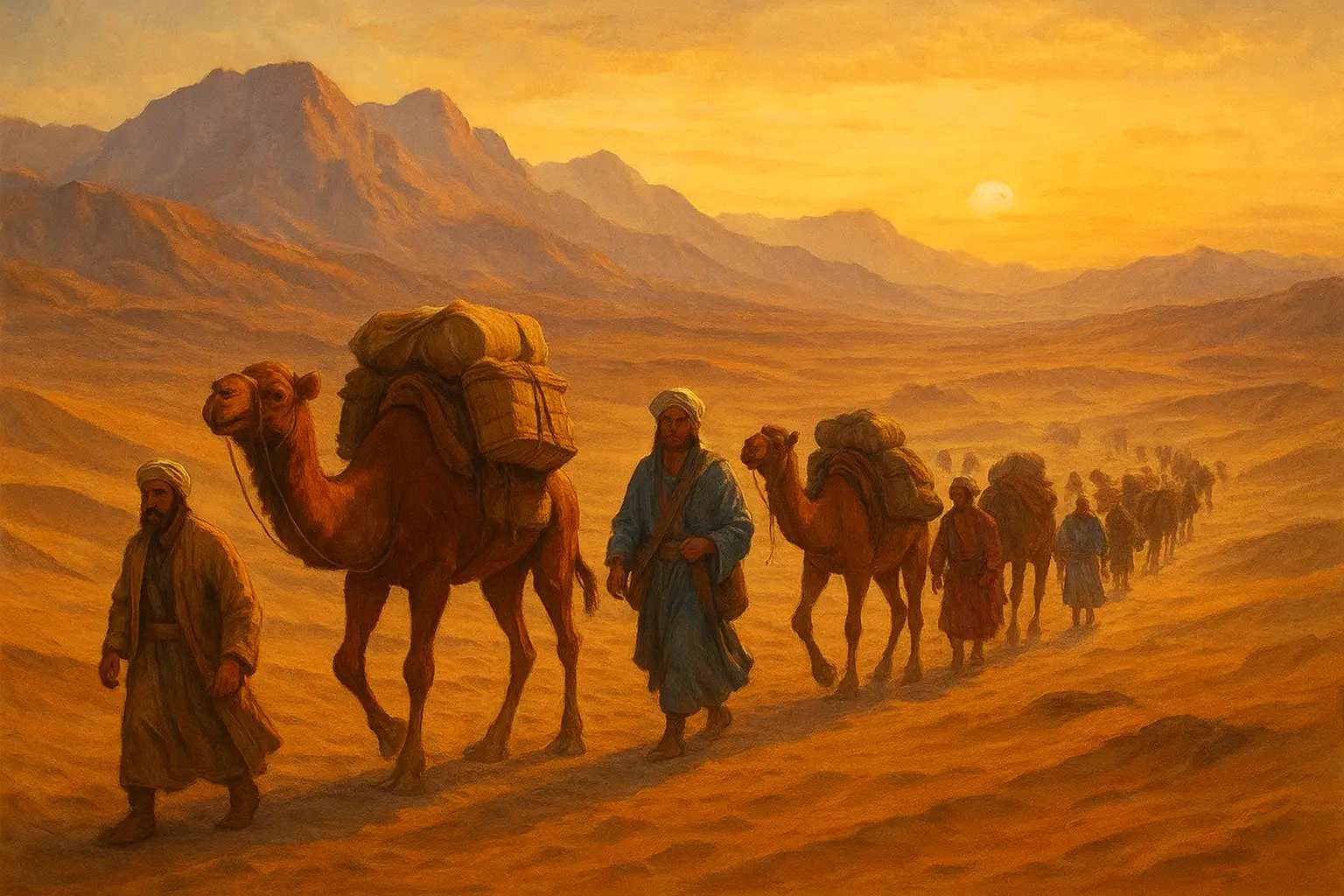

Challenges and Dangers

Traveling the Silk Road was perilous. Merchants faced:

- Harsh deserts like the Taklamakan, called the “Place of No Return.”

- Bandits and raiders, especially along mountain passes.

- Political instability as empires rose and fell.

- Diseases — the Black Death, which swept through Eurasia in the 14th century, likely traveled from Central Asia along trade routes.

Caravans moved slowly, often taking months or years to reach their destination. Yet the potential rewards — in wealth, fame, and knowledge — kept merchants on the move.

The Decline of the Silk Road

By the 15th century, the Silk Road’s dominance began to wane due to several key factors:

- The Rise of Maritime Trade

European explorers, such as Vasco da Gama, discovered new sea routes to Asia around the Cape of Good Hope, bypassing the land-based Silk Road altogether. - The Fall of Empires

The Mongol Empire fragmented, and wars between the Ming Dynasty, Timurids, and Ottoman Empire disrupted overland routes. - Insecurity and Decline in Demand

Overland routes became unsafe, while sea trade proved faster, cheaper, and capable of carrying larger quantities of goods.

By the time the Age of Discovery began, the Silk Road had faded into legend — replaced by ships and sea lanes that would define the modern world economy.

The Legacy of the Silk Road

Though the physical routes declined, the legacy of the Silk Road endures.

1. Cultural Fusion

The Silk Road laid the foundations for centuries of cultural blending. Languages, cuisines, and traditions across Eurasia still reflect ancient connections — from Persian carpets in China to noodles that inspired Italian pasta.

2. Technological and Scientific Exchange

Inventions like paper, compass navigation, and printing traveled westward, profoundly shaping European development. Likewise, astronomy, mathematics, and medicine from the Islamic world influenced Asian scholarship.

3. Modern Revivals

Today, governments seek to revive the Silk Road’s spirit of connectivity. China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), launched in 2013, aims to rebuild trade networks linking Asia, Africa, and Europe — echoing the routes of the ancient Silk Road.

Though politically and economically complex, this modern project reminds the world of the enduring power of trade to connect civilizations.

The Silk Road and the Birth of Globalization

Modern globalization — the free flow of goods, ideas, and people — owes its roots to the Silk Road.

It taught humanity that:

- Trade is not merely economic but cultural.

- Diversity and cooperation drive innovation.

- Borders are porous when curiosity outweighs fear.

The Silk Road’s legacy is a testament to the fact that the world has always been interconnected, long before the internet or modern trade agreements.

Conclusion

The Silk Road was far more than a trade route — it was the first global network of exchange, linking empires, religions, and cultures across thousands of miles.

Through deserts, mountains, and seas, caravans carried not only silk and spices but also the dreams and ideas that shaped civilization itself.

Its story is one of resilience and curiosity — proof that humanity’s greatest achievements often emerge from the meeting of worlds.

As we look to the future of global cooperation, the Silk Road reminds us that connection — not isolation — has always been our most valuable path forward.