Introduction

Throughout human history, civilizations have risen, thrived, and fallen — leaving behind traces of brilliance that still puzzle us today. From the precise engineering of the Great Pyramid of Giza to the mysterious Antikythera Mechanism and the lost secrets of Damascus steel, ancient people achieved feats that seem far beyond their known technological capabilities.

How did societies thousands of years ago accomplish such marvels with the limited tools of their eras? Were they simply more advanced than we’ve imagined — or did humanity once possess scientific knowledge that has since been lost to time?

This article dives deep into the forgotten technologies of the ancient world, exploring real archaeological evidence, scholarly interpretations, and ongoing debates about whether modern science is still catching up to what the ancients already knew.

1. The Antikythera Mechanism — The World’s First Computer

In 1901, Greek sponge divers discovered a corroded lump of bronze among the remains of an ancient shipwreck near Antikythera Island, between Crete and mainland Greece. When archaeologists examined it, they found an astonishing device: a complex system of gears, dials, and inscriptions — clearly mechanical in nature.

Decades of research revealed that the Antikythera Mechanism, built around 150–100 BCE, was a sophisticated astronomical calculator capable of predicting solar and lunar eclipses, tracking planetary movements, and possibly even forecasting the timing of Olympic Games.

X-ray scans have shown over 30 precision bronze gears, crafted with astonishing accuracy — something thought impossible in that era. It predated the next comparable mechanical clock by over a thousand years.

Modern scientists often call it the world’s first analog computer. It suggests that ancient Greeks possessed not only theoretical knowledge of astronomy but also advanced mechanical engineering far ahead of its time.

How was such technology forgotten? Historians suspect that the fall of the Roman Empire and subsequent centuries of turmoil erased this specialized knowledge, leaving Europe without complex mechanical devices until the medieval period.

2. The Lost Art of Damascus Steel

For centuries, blades made from Damascus steel were legendary. Produced in the Middle East from around 300 CE until the 18th century, they were famed for their superior strength, flexibility, and distinctive wavy patterns.

Warriors from the Crusades to the Mughal Empire praised these swords as capable of slicing through iron helmets or striking sparks from stone without dulling. The steel’s exact composition and forging process became a closely guarded secret, passed from master to apprentice — until it was lost altogether by the 1700s.

Modern metallurgists have attempted to recreate Damascus steel using ancient texts and surviving blades. Studies using electron microscopy have revealed nanostructures of carbon nanotubes within the metal — microscopic features that modern nanotechnology only rediscovered in the 20th century.

The secret likely lay in the Wootz steel imported from India, combined with precise heat treatments and impurities like vanadium. But despite centuries of research, no one has yet replicated the true original formula. It stands as a striking example of forgotten scientific mastery — a metallurgical art centuries ahead of its time.

3. The Great Pyramid of Giza — An Engineering Enigma

Built around 2560 BCE, the Great Pyramid of Khufu remains one of the most astonishing engineering achievements in human history. Weighing 6.5 million tons and originally standing 481 feet tall, it was the tallest structure on Earth for over 3,800 years.

The pyramid’s precision continues to baffle experts. The base is almost perfectly square, aligned to true north with a deviation of less than 1/15th of a degree — an accuracy that rivals modern surveying tools. Each side was once covered with smooth limestone casing stones, cut so precisely that even a razor blade could barely fit between them.

Despite centuries of study, how the pyramid was built remains uncertain. Traditional theories propose ramps, levers, and massive labor forces. Yet no conclusive archaeological evidence of such large-scale ramps has ever been found.

What’s more, the pyramid’s internal chambers show advanced understanding of geometry, resonance, and possibly even energy dynamics. Recent studies using muon radiography have uncovered hidden voids inside the structure, suggesting that the ancient Egyptians possessed engineering methods we still don’t fully comprehend.

Some fringe theorists have speculated about lost construction technologies or acoustic levitation, though mainstream archaeology attributes it to immense human labor and ingenuity. Still, the precision of this 4,500-year-old monument continues to defy easy explanation.

4. Roman Concrete — Stronger Than Modern Concrete

The Romans were master builders, and their enduring structures — aqueducts, domes, and harbors — are living proof. Many of their constructions, including the Pantheon and Colosseum, still stand after nearly 2,000 years.

The secret lies in their concrete, which was not rediscovered until recently. Modern concrete typically lasts about 50–100 years before showing cracks. Roman concrete, by contrast, has survived millennia, even in harsh marine environments.

Recent studies led by MIT researchers revealed that Roman concrete contained lime clasts — reactive calcium oxide particles that allowed the material to “self-heal” when exposed to moisture. When cracks formed, the lime would react with water and carbon dioxide, sealing the fissures naturally.

Their unique mixture of volcanic ash, lime, and seawater produced a durable mineral called Al-tobermorite, giving Roman concrete its resilience. Ironically, after the fall of Rome, this formula was forgotten, and concrete technology regressed for over a thousand years until rediscovered in the 19th century.

5. The Greek Fire — The Lost Weapon of the Byzantines

In the 7th century CE, the Byzantine Empire unveiled a terrifying weapon known as Greek Fire — a liquid substance that could be sprayed onto enemy ships and continued to burn even on water. It was so feared that it gave Byzantium naval dominance for centuries.

The exact composition of Greek Fire remains unknown. Ancient chroniclers described it as an unquenchable flame, ignited by water contact and possibly made from ingredients like naphtha, sulfur, quicklime, or petroleum.

Its formula was a closely guarded state secret, passed only to trusted engineers. When the Byzantine Empire eventually fell in 1453, the recipe was lost forever.

Modern chemists have proposed several possible mixtures, but none have reproduced the described effects. Greek Fire remains one of history’s most closely kept technological mysteries, an early example of chemical warfare centuries before gunpowder.

6. The Baghdad Battery — Ancient Electricity?

Discovered near Baghdad in the 1930s, the so-called Baghdad Battery is a small clay jar containing a copper cylinder and an iron rod. When filled with an acidic liquid such as vinegar or wine, it can produce a small electric current — similar to a primitive battery.

Dating to around 200 BCE–200 CE, the artifact’s purpose remains debated. Some believe it was used for electroplating metals (coating gold or silver onto objects), while others argue it served as a simple storage container.

Although there’s no solid proof of electrical use, the Baghdad Battery exemplifies how ancient artisans may have stumbled upon electrochemical principles long before modern science formalized them. Whether deliberate or coincidental, it hints that humanity may have experimented with electricity nearly two millennia earlier than we thought.

7. The Lost City of Nan Madol — The Pacific’s Forgotten Engineers

Off the coast of Pohnpei in Micronesia lies Nan Madol, an ancient city built on a series of 100 artificial islets made from massive basalt columns — some weighing up to 50 tons. The site dates back to around 1200 CE, though local legends suggest it is far older.

Archaeologists remain puzzled about how the builders transported and positioned these stones across the water without cranes, wheels, or iron tools. Oral traditions claim the stones were moved “by magic” or through levitation, though researchers suspect ingenious methods using buoyancy and logs.

Nan Madol, often called the “Venice of the Pacific,” remains a striking testament to a lost engineering culture — one that built monumental architecture in total isolation from the rest of the world.

8. Other Forgotten Inventions

History hints at countless other lost technologies:

- Chinese seismographs from 132 CE could detect earthquakes hundreds of miles away.

- Greek automata — mechanical statues and doors operated by air pressure or steam.

- Incan earthquake-resistant architecture, achieved without mortar yet capable of withstanding centuries of seismic activity.

- Maya blue pigment, a vibrant, chemically stable dye whose production technique disappeared after the Spanish conquest.

Each example shows that ancient civilizations weren’t primitive — they were creative problem solvers, many of whose methods were never fully recorded or transmitted.

Conclusion

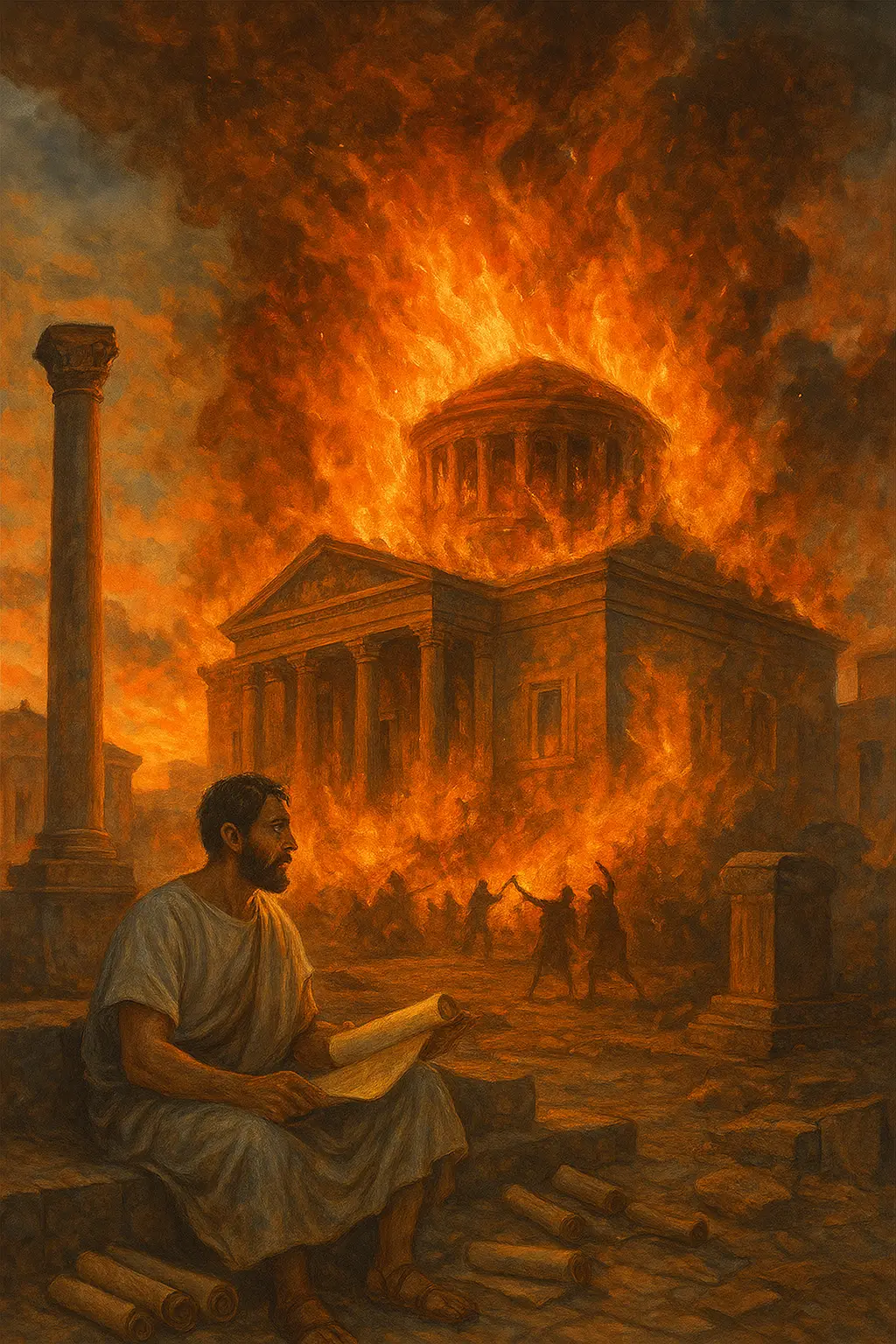

The lost technologies of the ancient world remind us that progress is not a straight line. Civilizations rise, fall, and often take their secrets with them. Knowledge is fragile — a single war, fire, or cultural shift can erase centuries of innovation.

From the gears of the Antikythera Mechanism to the indestructible Roman concrete, these remnants challenge our assumptions about ancient intelligence. They show that human ingenuity has always been extraordinary, and that rediscovering forgotten knowledge can unlock doors to the future.

As we explore these mysteries, we’re not just studying history — we’re reconnecting with the genius of our ancestors, whose understanding of nature, materials, and mechanics still has lessons for us today.

Perhaps the greatest mystery of all is how much more remains buried — waiting to be rediscovered beneath the sands, stones, and oceans of time.