Introduction

The story of human civilization has often been told as a triumph of people over nature — humans taming rivers, building cities, and mastering agriculture. But what if one of the world’s first civilizations wasn’t simply a result of human brilliance, but also the rhythm of the sea itself?

In the heart of ancient Mesopotamia, the Sumerian civilization — often called the “cradle of civilization” — emerged around 4500 BCE. Cities like Uruk, Ur, and Lagash introduced innovations such as writing, governance, architecture, and organized religion. Yet a recent wave of scientific studies is challenging our long-held understanding of how Sumer came to be.

Research led by teams from the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution and Clemson University (published October 2025) proposes that tidal rhythms and natural deltaic processes played a central role in nurturing the earliest stages of Sumerian agriculture and urban life. These findings suggest that the environment wasn’t just a backdrop — it was a co-architect of civilization itself.

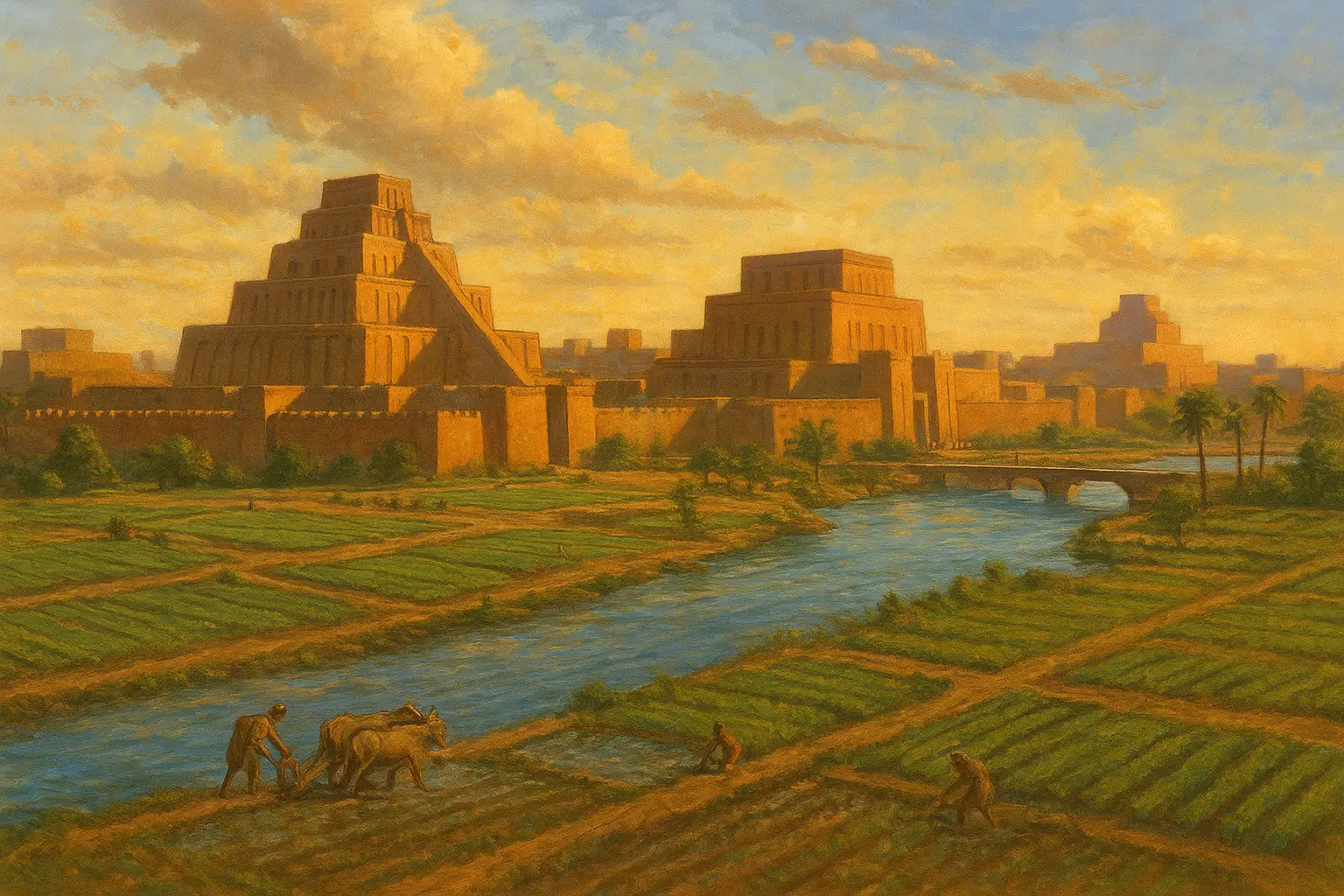

The Birth of Sumer: Where the Rivers Met the Sea

Sumer occupied the southern reaches of Mesopotamia — roughly modern-day southern Iraq — between the Tigris and Euphrates Rivers. Around 7000 years ago, the Persian Gulf stretched much farther inland than it does today, turning the lower Mesopotamian plain into a vast wetland environment rich in fish, reeds, and fertile soil.

This region was a paradise for early farmers. Seasonal flooding deposited nutrient-rich silt, and early inhabitants learned to harness these conditions through small-scale irrigation. But the new research reveals something more: the Gulf’s tides reached deep inland, influencing the flow of water across the plains twice daily.

According to sediment analysis and hydrodynamic modeling, these tidal surges provided predictable, gentle inundation — a “natural irrigation system” that required minimal human engineering. In other words, the first agricultural villages didn’t need massive canal systems; they relied on the rhythms of the Earth.

This revelation changes our entire view of how urban life began. Civilization may have started not with control over nature, but with harmony with it.

Tidal Agriculture: Nature’s Hidden Infrastructure

The tidal theory challenges the traditional view that Mesopotamian farmers invented complex irrigation networks early on. Instead, the earliest Sumerian settlements — around 6000 to 4500 BCE — might have flourished because the environment provided them with ready-made water management.

As the tides came in, they flooded shallow basins and low-lying fields; as they receded, they left behind moisture and silt, perfect for early grain cultivation. This allowed communities to grow crops such as emmer wheat and barley with minimal effort, leading to reliable food surpluses and, eventually, population growth.

When the tides were at their strongest, water levels rose predictably — enabling the first farmers to plan their planting and harvesting cycles with accuracy. Archaeological evidence of early canal channels near Eridu and Ur shows that these waterways were short and irregular — consistent with systems that enhanced natural tides, not replaced them.

The Sumerians’ early success, therefore, may have stemmed from an intuitive understanding of nature’s patterns.

The Turning Point: When the Tides Receded

But nature’s gift wasn’t eternal. Around 5000 years ago, the Persian Gulf began to recede due to natural sediment build-up and climatic shifts. As the shoreline retreated southward, tidal influence diminished. The fertile wetlands dried, and the rivers began to meander across a broader floodplain.

For the Sumerians, this environmental shift was a crisis — and an opportunity. Without the tides, natural irrigation ceased. To survive, communities had to build and maintain artificial canals, levees, and reservoirs. This marked the birth of engineered irrigation.

Archaeological and textual records — such as the Code of Ur-Nammu and early Sumerian administrative tablets — show increasing attention to water control, boundary disputes, and labor coordination for canal maintenance. The complexity of water management led to bureaucratic organization, state authority, and specialized labor.

In short, environmental change forced human innovation. The decline of tidal irrigation catalyzed the very features that define civilization: government, law, writing, and cities.

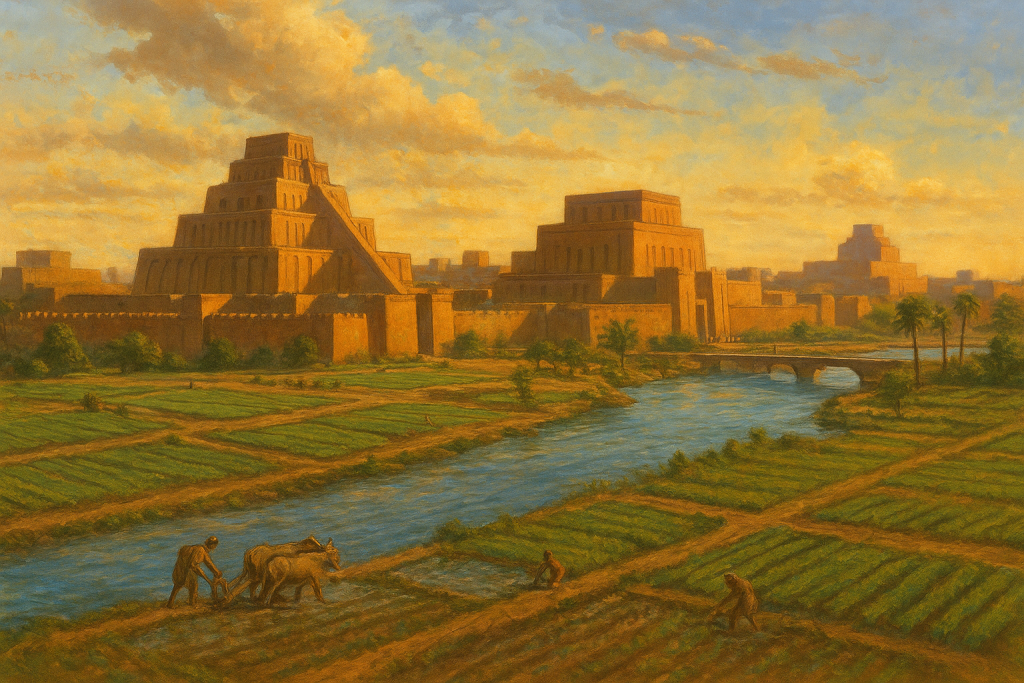

The Rise of Cities and the Sumerian Golden Age

By 3100 BCE, Sumer had entered its golden age. Cities such as Uruk, Ur, Lagash, Eridu, and Kish thrived as centers of trade, worship, and governance.

- Uruk, often considered the world’s first true city, housed perhaps 50,000 inhabitants at its height. It boasted monumental architecture such as the White Temple and Eanna District, dedicated to the goddess Inanna.

- Cuneiform writing emerged around the same time, initially for recording grain rations and trade goods — an innovation born from the need to manage increasingly complex resource systems.

- Trade networks expanded, connecting Sumer with regions as far as the Indus Valley and Anatolia.

All of these developments stemmed from the necessity of managing water — a problem that arose only when the natural tidal system disappeared. Civilization, it seems, was born from adaptation.

The Environment in Myth and Memory

The Sumerians’ religious and mythological texts preserve echoes of their tidal past. Their myths are filled with imagery of floods, waters, and divine control over the natural world:

- The Epic of Gilgamesh tells of a catastrophic flood that nearly wipes out humanity — likely inspired by ancient tidal inundations or flood events.

- Gods such as Enki (Ea), the deity of water and wisdom, and Enlil, lord of the atmosphere, dominate the pantheon — reflecting an enduring reverence for environmental forces.

- Temples were often constructed atop raised platforms (ziggurats), symbolizing humanity’s link between the heavens and the watery earth below.

Even as they mastered irrigation and built monumental cities, the Sumerians never forgot that nature was the original power behind their prosperity.

Scientific Evidence Behind the Tidal Hypothesis

The tidal hypothesis isn’t just poetic speculation — it’s grounded in rigorous science.

Researchers used core sediment analysis, hydrodynamic simulations, and satellite mapping of ancient riverbeds. Their findings, published in Science Advances (2025), revealed:

- Sediment layers containing marine microfossils hundreds of kilometers inland — proof that tidal waters once reached those areas.

- Alternating bands of silty and sandy deposits consistent with cyclical tidal inundation, rather than seasonal floods alone.

- Radiocarbon dating aligning with early settlement layers, indicating that humans occupied these regions during the period of tidal activity.

This data suggests that ancient farmers strategically positioned their settlements to exploit the unique tidal flows of the early Mesopotamian delta — a partnership between humanity and the sea.

A Global Pattern: Nature as Civilization’s Partner

The tidal model of Sumer invites us to rethink how civilizations everywhere might have formed. Environmental rhythms — tides, monsoons, river floods — may have been the true catalysts of early complex societies.

- In ancient Egypt, the predictable flooding of the Nile created a similar natural irrigation system that sustained agriculture for millennia.

- In the Indus Valley, monsoon-fed rivers enabled urban centers like Mohenjo-Daro and Harappa.

- In China’s Yellow River basin, sediment cycles shaped early state formation and agricultural innovation.

In all these cases, humans didn’t initially “conquer” nature; they cooperated with it — until environmental changes forced new adaptations.

Lessons for the Modern World

The Sumerian story offers a profound lesson for today. Our modern civilizations also depend on stable natural systems — climate, water cycles, fertile land. When those systems shift, as they did for the Sumerians, adaptation becomes essential.

Just as the end of tidal irrigation gave rise to the world’s first cities, modern climate shifts may drive humanity toward new forms of innovation and cooperation. Civilization, it seems, thrives not by resisting nature, but by learning to change with it.

Conclusion

The rise of Sumer wasn’t just the birth of civilization — it was the birth of a relationship between humans and the environment. The tides of the Persian Gulf provided a natural infrastructure that allowed agriculture and settlement to flourish. When those tides receded, humans responded with creativity, engineering, and social organization — the building blocks of urban life.

Far from being a mere backdrop, nature was an active participant in humanity’s first great leap forward. The rhythm of the tides shaped the rhythm of civilization itself.

Today, as we face environmental challenges of our own, the story of Sumer reminds us of a timeless truth: progress is not domination over nature — it is partnership with it.